About Lule Sami

The Sami are an indigenous people living in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia. Their territory stretches from the Kola peninsula in northwestern Russia to Engerdal in southern Norway and Idre in southern Sweden. This area is called Sápmi in the Northern Sami language. Traditionally, the Sami have lived by reindeer herding, fishing, hunting and farming, but today, they have both traditional and modern jobs. There are many interesting sites about Sami and the Sami people that you can visit online. For an overview over the links that we found useful please go to ==Lule Saami online==

BREIF HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Saami people have been on the Scandinavian and Kola Peninsulas in Northwest Europe since prehistoric times. Recent genetic (Niskanen 2002; Tambets, et al. 2004), archeological (Broadbent 2004; Zorich 2008) and linguistic research (Sammallahti 1998; Aikio 2006, 2007a, b) suggests that they are descendent of the first inhabitants of the area after the glaciers of the last ice-age receded.

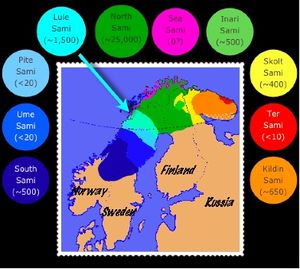

Archeological and historical evidence shows that the area traditionally inhabited by the Saami (“Sábme” in the Lule Saami language and “Sápmi” in the North Saami language) extends along most of the western coast of Norway, along most of the western coast of the Gulf of Bothnia in Sweden (Broadbent 2004; Zorich 2008) and well into Hedmark in Norway and southern Dalarna in Sweden (Hallerdal 1998a, b, c). The full extent of Sábme in Sweden is shown on the following map, but it is not shown on most modern maps for political reasons (Broadbent 2004). The Saami have also lived farther east and south in Finland than is shown here.

Although the Saami languages have a quite complicated history (Sammallahti 1998; Aikio 2006, 2007a, b), they are traditionally classified as belonging to the Uralic language family and are thus claimed to be unrelated to most of the other languages in Western Europe. Current theories suggest that their closest linguistic relatives are the Balto-Finnic languages - Finnish and Estonian (Sammallahit 1998, Aikio 2007a, b) and that the ancestors of the modern Saami and Balto-Finnic languages separated from one another more than 3,000 years ago. This means that the Saami language group is as old as the Germanic language group, which includes German, English, Dutch, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish (The New Encyclopædia Britannica 1993) and twice as old as the Romance language group, which includes Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian (Palmer 1954). The long history of the Saami languages, the fact that they are to a large extent mutually unintelligible, and a range of other considerations leads many linguists to classify them into several distinct languages rather than different dialects as they are often described (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialect for a general discussion of the dialect versus language controversy).

Although the Saami languages are classified as Finno-Ugric, their vocabularies are heavily influenced by contact with Slavic and Germanic neighbors (Aikio 2006, 2007a, b). In addition, recent research suggests that they also contain remnants of the original Paleolithic languages of Scandinavia (Aikio 2007 a, b). This supports the results of genetic studies suggesting that the origin of the Saami people is not co-extensive with the origin of the Finno-Ugric aspects of the Saami languages (Tambets, et al. 2004).

Linguists currently recognize nine living Saami languages (UNESCO 1993). A rough estimate of the traditional locations and number of speakers of these languages in shown on the map.

The Saami languages are usually discussed as forming two main groups based on geographic, historic and linguistic relatedness. These are Eastern (Inari, Kildin, Skolt, Ter) and Western (Lule, North, Pite, South) (Sammallahti 1998). Note that although the Sea Saami people seem to once have had an independent language that has been argued to be belong to either the Eastern Saami or Western Saami group (Ravila 1932; Hansegård 1966; Bergsland 1967), several centuries of social pressure have resulted in the Sea Saami adopting the North Saami, Lule Saami and/or Norwegian languages.

In addition to the nine living Saami languages, Akkala Saami (not shown on the map) was once spoken in Russia but died in 2003 when the last speaker died (http://www.galdu.org/govat/doc/nordisk_samekonvensjon.pdf).

Current Endangerment Status

Because of its long independent history, the relatively few number of speakers (i.e. less than 30,000 total), and the fact that very few children learn Saami, the Saami language family is arguable the most endangered language family in Europe (UNESCO 1993).

Lule Saami Language

Lule Saami is a member of the Western Saami language group (Sammallahti 1998), is the second largest of the Saami languages (UNESCO 1993), and is spoken by about 1,500 people. As shown on the map, the traditional Lule Saami area runs in an east-west band from Luleå in Sweden to Nordland in Norway.

According to the UNESCO Red Book of Endangered Languages (UNESCO 1993), Lule Saami is listed as seriously endangered. Following UNESCO’s new 9-factor evaluation, we give it a rating of severely endangered.

As with all languages, Lule Saami contains a complex dialect continuum that is the result of geographical, historical and sociological factors. Particularly in those areas where there is significant contact between speakers of Lule Saami and other Saami languages, there is greater similarity among languages and greater mutual intelligibility (e.g. see Grundström (1946:II) and Collinder (1949:x) for and example of North Saami influence on Lule Saami in Gällivare). This often leads to the impression that Lule Saami and North Saami are mutually intelligable and thus might be considered different dialects of a single language. However, without special training or a history of contact with one another’s languages, it is quite difficult for Lule Saami and North Saami to converse with one another using their respective languages, and they resort to using a North Germanic language (Norwegian and/or Swedish). One might compare this aspect of the relationship between Lule Saami and North Saami with that between German and Dutch (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dialect#Dialect_continuum).

Summary

The Saami languages have a quite complicated history that stretches back millennia, and yet they form the most endangered language group in Europe. Lule Saami is one of nine living Saami languages, it belongs to the Western Saami group and it is spoken by fewer than 1,500 speakers in Norway and Sweden.

References

Aikio, A. 2006. On Germanic-Saami contacts and Saami prehistory. — Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 91: 9–55. http://www.sgr.fi/susa/91/aikio.pdf Aikio, A. 2007a. The study of Saami substrate toponyms in Finland. — Ritva Liisa Pitkänen & Janne Saarikivi (eds.), The borrowing of place-names in the Uralic languages. Onomastica Uralica 4, pp. 159–197. Debrecen / Helsinki. http://mnytud.arts.klte.hu/onomural/kotetek/ou4/08aikio.pdf Aikio, A. 2007b. Etymological nativization of loanwords: a case study of Saami and Finnish. — Ida Toivonen & Diane Nelson (eds.), Saami Linguistics, pp. 17–52. John Benjamins. http://cc.oulu.fi/~anaikio/etym_nativ_preprint.pdf Bergsland, K. 1967. Lapp Dialect groups and problems of history. In Lapps and Norsemen in olden times. Broadbent, N. 2004. Saami prehistory, identity and rights in Sweden. Presented at the Third Northern Research Forum. Yellowknife, Canada. http://old.nrf.is/Publications/The%20Resilient%20North/Plenary%203/3rd%20NRF_plenary%203_Broadbent_final.pdf Hallerdal, S. 1998a. Samer Dalarnas urinvånare. http://arkiv.daltid.se/1998/06/19980609/FK-19980609-17.pdf Hallerdal, S. 1998b. I spåren efter K E Forsslund. http://arkiv.daltid.se/1998/07/19980731/FK-19980731-15.pdf Hallerdal, S. 1998c. Etnisk rensning av samer i Dalarna. http://arkiv.daltid.se/1998/07/19980731/FK-19980731-15.pdf Hansegård, N. 1966. Sea lappish and moutain lappish Niskanen, M. 2002. "The Origin of the Baltic-Finns". The Mankind Quarterly Vol. XLIII Number 2. http://www.mankindquarterly.org/samples/niskanenbalticcorrected.pdf Nordisk samekonvensjon. 2005. http://www.galdu.org/govat/doc/nordisk_samekonvensjon.pdf Palmer, L. R. 1954. The Latin Language. Repr. 1988, Univ. Oklahoma. Qvigstad, 1925. Die lappischen dialekte in Norwegen. Ravila, P. 1932. Das quantitätssystem des seelappischen dialektes von Maattivuono. Sammallahti, Pekka. 1988. “Historical phonology of the Uralic languages”. The Uralic Languages, ed. by Denis Sinor. 478–554. E.J. Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands. Sammallahti, Pekka. 1998. The Saami Languages: an Introduction. Kárášjohka, Norway: Davvi Girji. Tambets, K, et al. 2004. The Western and Eastern Roots of the Saami—the Story of Genetic “Outliers” Told by Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosomes Am J Hum Genet. 74(4): 661–682. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1181943 The New Encyclopædia Britannica. 1993. "Languages of the World: Germanic languages". Chicago, IL, United States: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. UNESCO. 1993. Red Book on Endangered Languages. http://www.helsinki.fi/~tasalmin/europe_report.html UNESCO. 2003. Language Vitality and Endangerment. Zorich, Z. 2008. Native Sweden. ARCHAEOLOGY Vol. 61 Number 4. http://www.archaeology.org/0807/abstracts/sweden.html